| Lesson 9 | Client/Server Services and Inetd-Style Activation |

| Objective | Describe how server processes start and stop under the control of inetd (and its modern equivalents). |

Clients, Servers, and Ports

Most network services follow a predictable pattern: a client initiates a connection to a server over a well-known TCP or UDP port. The server process accepts the request, performs work, and returns a response. This lesson uses Telnet as a historical example to teach the mechanics of client/server networking, and then updates the workflow to modern Linux service management.

Important security note: Telnet transmits credentials and data in cleartext and should not be used for remote login on modern networks. Today, SSH and TLS-based services are standard. Telnet still has value as a diagnostic technique for testing whether a TCP port is reachable—provided you understand the risk and avoid sending secrets.

Client/Server in Practice

When you access a remote service, you typically have:

- Client process — runs on your workstation and initiates a connection (browser, ssh client, curl, etc.)

- Server process (daemon) — runs on the remote host and listens on a port (sshd, nginx, postfix, etc.)

- Transport protocol — TCP (connection-oriented) or UDP (message-oriented)

- Port number — identifies the service endpoint (e.g., 22 for SSH, 443 for HTTPS)

The mapping between common services and port numbers is traditionally documented in /etc/services. While many modern applications ship with their own configuration defaults, /etc/services remains a useful reference during troubleshooting.

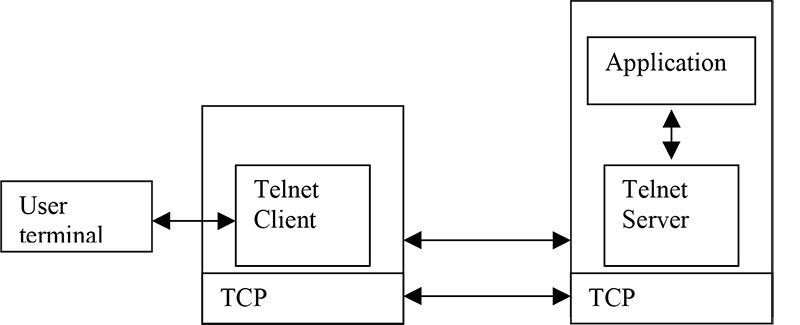

Telnet as a Historical Model

Telnet is a classic example of a TCP client/server service. A Telnet client connects to a server listening on TCP port 23. The server accepts keystrokes from the client and returns output as if the user were interacting with a terminal session on the remote machine.

In the original Telnet model:

- The client provides a text terminal interface.

- The server performs “terminal emulation” on the remote host.

- Both sides negotiate terminal capabilities using a Network Virtual Terminal (NVT) abstraction.

How Server Processes Start and Stop

This is the core lesson objective: understanding how the server-side process is activated. Historically, UNIX systems used a “super-server” model so that every service did not need to run continuously.

The inetd Super-Server Model (Legacy)

With inetd, the system listens for connections on multiple ports. When a request arrives for a configured service, inetd

spawns the appropriate server process, connects the process to the network socket, and then the server handles the session.

When the session ends, the process exits.

In other words:

- No active daemon required for every service.

- inetd listens on behalf of many services.

- Server process is spawned on-demand and stops when the request completes.

This saved memory and CPU on older hardware—but it also created security and management challenges as services grew more complex. Modern systems typically use stronger service supervision and access controls.

Modern Replacement: systemd Service and Socket Activation

On most contemporary Linux distributions, systemd replaces traditional init scripts and often replaces inetd-style dispatching.

You’ll commonly encounter two modern patterns:

- Service activation: the daemon runs continuously and

systemdsupervises it (restart on failure, logs, dependencies). - Socket activation:

systemdlistens on a socket (like inetd did) and starts the service only when traffic arrives.

Socket activation is the direct conceptual successor to inetd. It provides the same “start on demand” behavior, but with better logging, dependency control, privilege separation, and predictable lifecycle management.

As a Linux network administrator, it’s worth learning to recognize which model a service uses because it changes what you troubleshoot:

- If a service is socket-activated, it may not appear “running” until the first connection occurs.

- If a service is always-on, you troubleshoot via its unit file, logs, and runtime status.

Ports, Testing, and Safer Tools Than Telnet

Even though Telnet is obsolete for authentication, the idea of “connect to a host:port and see if it responds” is still useful. Today you typically use:

ss -tulpnto view listening sockets and the owning processsystemctl statusandjournalctlto inspect service state and logsnc(netcat) to test TCP port connectivity without invoking a legacy login protocolcurlto test HTTP/HTTPS services with visibility into headers and TLS

If you do use a Telnet-style connectivity test, treat it as a port probe, not a login method. For example, connecting to a web server’s port can confirm routing and firewall behavior.

Here is a legacy-style example of probing an HTTP port:

INPUT:

telnet www.dispersednet.com 80A safer modern alternative is:

nc -vz www.dispersednet.com 80That command checks whether the TCP port is reachable without starting a Telnet session.

Client/Server “Transactions” on the Web

When people describe “transactions” in client/server systems, they’re often referring to a single request/response cycle: a client sends a request, the server processes it, and a response is returned. In web services, this is typically HTTP. On the server side, request handling often triggers work such as authentication checks, database reads/writes, and logging.

In modern production environments, server-side “transactions” should be protected with encryption (TLS), strong authentication (keys, tokens, MFA where applicable), and audited logging. Avoid obsolete cryptography such as DES; use modern ciphers (AES) and modern hashes (SHA-256 or stronger) when cryptographic primitives are involved.

The key takeaway for this lesson is that client/server communication is predictable, but the server activation model matters: inetd historically spawned services on demand, and today systemd can do the same via socket activation—or you may run a persistent daemon supervised by systemd.

The following series of images illustrates the classic Telnet client/server workflow: